Reposted with permission from Gavi.

Anand Kumar learned to walk later than other children. When he did, he walked with difficulty, dragging his right leg. He was around three years old when his parents reached out for a diagnosis. “I’m sure that they tried all the doctors in Bangalore to just get it corrected. But the thing was: couldn’t do it,” he says.

His route to being an athlete was not remotely expected when he was a toddler. The doctors’ verdict ruled out recovery. Kumar had suffered irreversible damage to both his right arm and right leg as a result of an infection with poliovirus during infancy. He was unlucky: in most babies, the disease would have passed all-but-unnoticed, mistakable for a bout of the flu. But approximately one in 200 poliomyelitis patients suffer permanent paralysis. Around 5 – 10% of people paralysed risk dying if the muscles in their respiratory systems are immobilised.

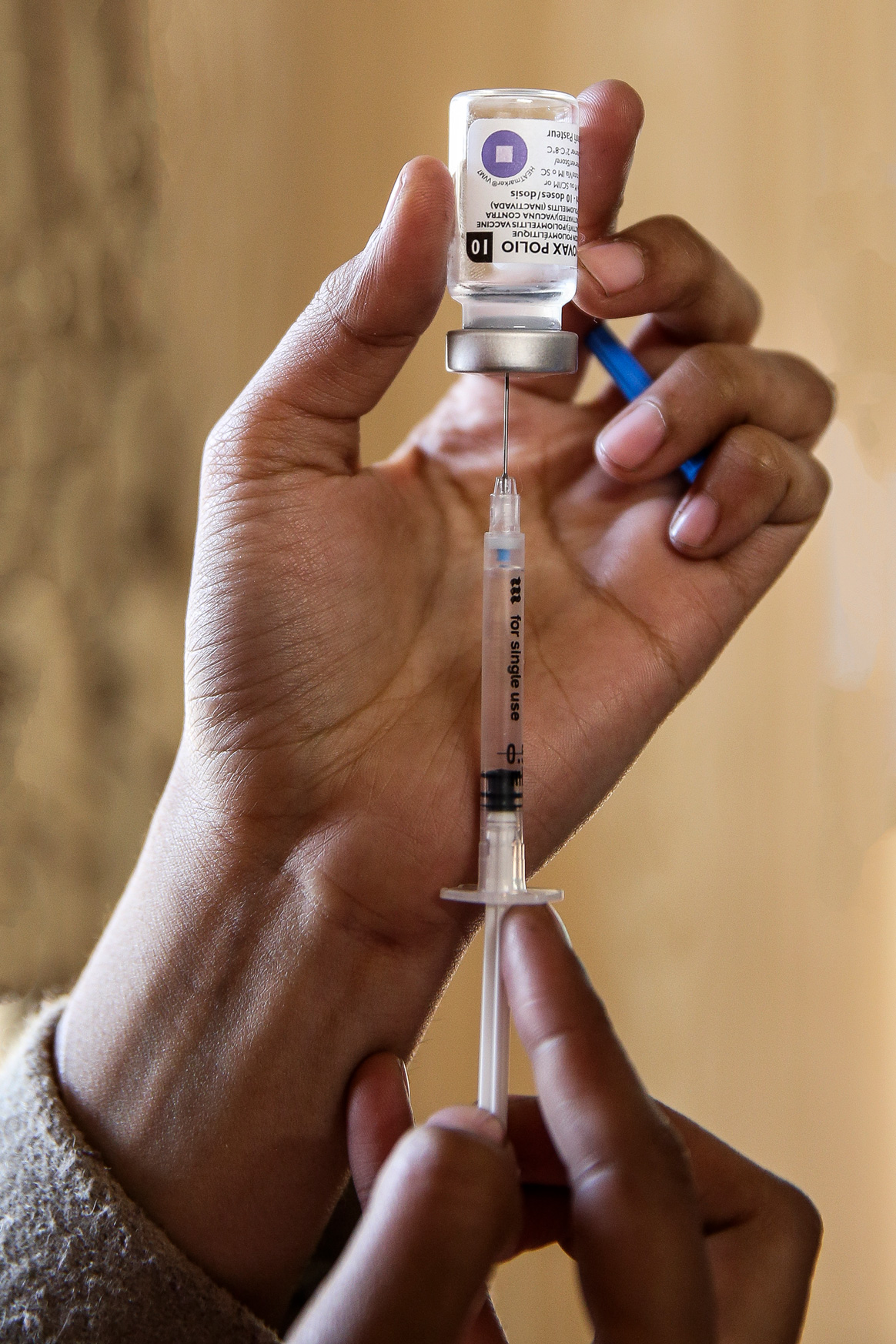

Although the world’s first safe and effective polio vaccine – the Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV)1 – had been introduced decades before, and countries like the USA were newly polio-free, in the early 1980s, just 2% of India’s children had been administered the recommended three doses. During 1981 alone, India recorded more than 38,000 polio cases. The real tally may have stood much higher: researchers have pegged the actual incidence during the 1980s at closer to 200,000 cases a year.

By 1990, the annual infection figures were in decline. But the trend towards zero cases was halting, and jagged. In 2002, India’s depleted but persistent polio case-load jumped six-fold. A year later, India was home to 83% of all the new polio cases in the world. Uttar Pradesh alone, the vast and troubled northern state in which UNICEF had recently been obliged to launch a social mobilisation scheme to counter vaccine hesitancy, accounted for 64% of the world’s polio burden. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative redoubled its immunisation efforts, but as certain leading anti-polio campaigners would later admit, to some onlookers, the challenges of elimination in India looked at times simply too steep to surmount.

Meanwhile, in the late 1990s, Anand Kumar was leaving school for college with the frustrated awareness that he had been passed over. “Due to my disability, I was not active like other kids, so I was not taken into consideration for cultural activities or sports,” he says. “I was feeling that I was missing something.”

As such, he found his way to badminton late: aged nineteen, years too old to be taken on as a beginner by the coaches he approached for training, but newly cognisant of the existence and possibilities of para-sport. He watched the coach at his local club from the bleachers – “luckily, the coach was a left-hander, and I’m always a left-hand player” – then practised the technique he observed on the court on his own. He improved quickly, began beating his able-bodied opponents.

In 2001, he was invited to represent India at a para-badminton tournament in Germany. “I thought, okay: I’m defeating the able-bodied players – and I can defeat the disabled players also.” Instead, he lost every match. Looking back, he calls it “a very good experience.” That was the year he decided to practice “most seriously.”

Success, Anand Kumar earnestly points out, has not come easily. “I have had to prove myself in each and every field,” he says. He meets young players inspired by his achievements – some 110 medals, including an Asian Games bronze, a BWF Para-Badminton World Championship doubles gold and a prestigious Ekalavya sporting award – “but I always like to share my other part of the story – which was very difficult, in which I struggled hard to come to this level,” he says. “Like, I started in the year 2001 to play an international tournament, but it took 15 long years to be a World Champion”.

That struggle has only been incidentally shaped by his disability, he clarifies. “Life is always challenging, whether it’s in an able body or a disabled body,” he says. The message he shares with the students he now coaches at his own Academy, able-bodied and disabled alike, is to take up life’s challenge with determination – put simply, to never give up.

Likewise, it took a number of tacks and switches to drive down polio in India – the introduction of improved bivalent polio vaccine in 2010; the institution of rolling vaccination at strategic transport hubs; hand-washing and sanitation campaigns to tackle the diarrhoea epidemic that was found to be weakening polio vaccine effectiveness, to name just a few – but in 2012, India finally arrived at zero polio cases.

“Today we are calling India polio-free,” Kumar says. “It’s only because of vaccination.” He’s right. But he’ll also tell you that no victory is ever quite that straightforward.