Addressing social norms

Giza, Egypt, is home to the ancient world-renowned pyramids and a medical marvel of the modern age — the accredited Polio Regional Reference Laboratory (RRL) at the Egyptian Holding Company for Biological Products and Vaccines (VACSERA). Director of the polio regional reference laboratory,

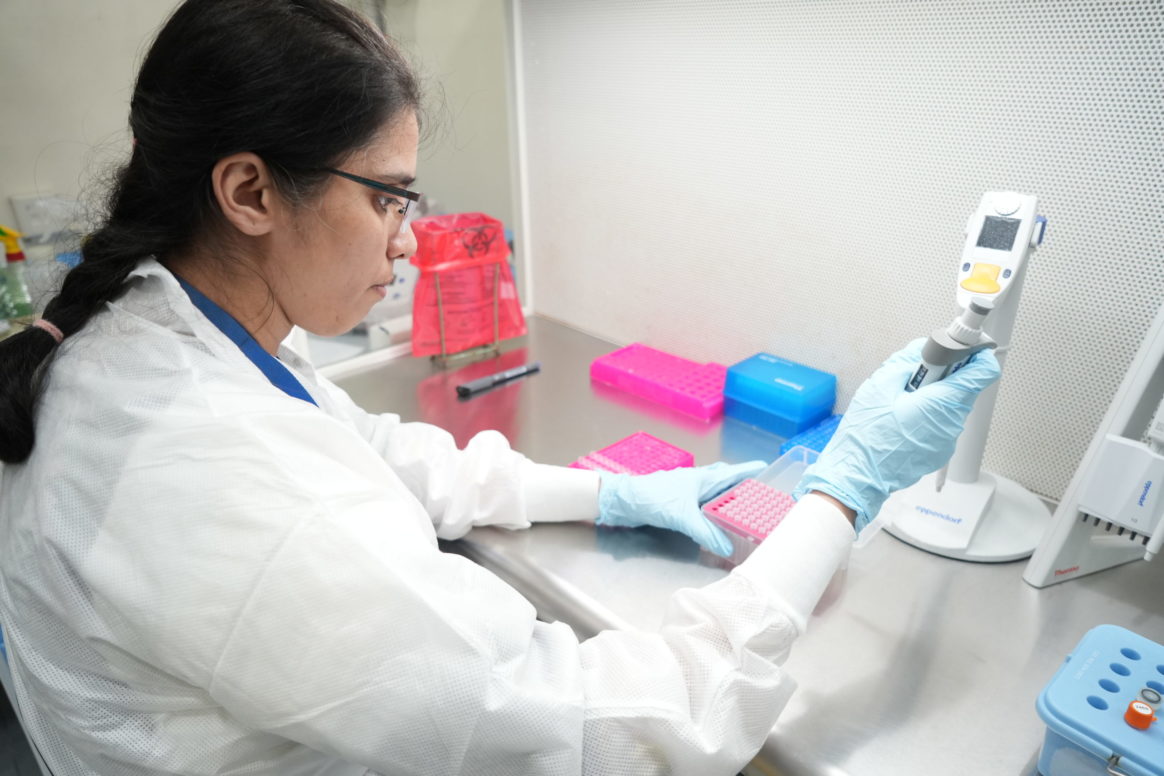

Amira Zaghloul oversees five different departments, working closely with her 25-member team. They regularly conduct poliovirus diagnostic tests on stool samples obtained from children as well as sewage samples from Egypt. Additionally, they carry out sequencing of samples that have been identified as positive for polio in Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Sudan, and Syria, which determines if the polioviruses confirmed are related to any other ones. Their goal is to meet tight deadlines, to swiftly respond to any detection of the poliovirus.

Like her counterparts across the Region, Ms Zaghloul and her colleagues rely on the latest laboratory and digital technology. With support from partners, they regularly upgrade their technology and skills to ensure the shortest possible time between sample collection and churning out results. Soon, for example, Ms Zaghloul and her team will acquire the next generation of sequencing technology – that will help test the entire genome of a virus, or genetic materials that make up a virus, and identify any mutations. This will also help to determine the origin of detected polioviruses, and track epidemiological patterns of spread.

Her work doesn’t come without challenges though. When she first took on this role, Ms Zaghloul faced negative social perceptions of being a female leader of a mixed team of men and women. To address this, Ms Zaghloul introduced rules and regulations that apply to all, regardless of age and gender.

People working in health should exemplify a spirit of perseverance, devotion, hope and ambition – regardless of their gender – she emphasizes.

Negotiating to receive samples for polio tests

When Dr Hanan Al Kindi finally settled on what to study − over virology, medicine or business — she had no idea she would need negotiation skills in her job. As the head of nine polio and measles laboratory departments that test samples from Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Yemen for polioviruses, Dr Al Kindi ensures everything runs like clockwork.

At times, this involves thinking out of the box. After noting huge time lags in the delivery of stool samples – used to test for polioviruses – from Yemen to Oman, Dr Al Kindi rolled up her sleeves and got to action. She learnt that after driving through mountains and deserts to reach Oman’s borders, the refrigerated trucks that transport stool samples were kept at the border for hours of inspection. Dr Al Kindi and her team got the contacts of officials at the border and invited them over for a chat.

Her determined negotiation skills and ability to read the room – to understand when peripheral stakeholders such as officials at the border and couriers needed more context about the laboratory’s role in saving children from polio — eventually helped reduce the red tape at the border. This means Dr Al Kindi and her team can test for polioviruses and turn over their results to the polio programme in Yemen in less time than before. This steers timely and appropriate outbreak response activities, including polio immunization campaigns to protect children from polio.

Working in an equitable environment

Dr Nayab Mahmood plays a vital role in ensuring samples are tested for poliovirus as swiftly as possible for timely interventions in Afghanistan and Pakistan – the only two countries left with naturally occurring poliovirus.

Dr Mahmood is a virologist serving the polio programme of the Regional Reference Polio Laboratory at Pakistan’s National Institutes of Health in Islamabad. Her role involves intricate technical procedures, including molecular diagnostics, and genetic sequencing of the poliovirus genome. This work helps to determine how wild polioviruses are spreading across both endemic countries.

Being part of an emergency programme means that Dr Mahmood and her colleagues need to be available 24 hours a day – a pace that is impossible to maintain without feeling an impact in one’s personal life. She feels that the best way to maintain a work-life balance is for each member of a team to communicate their needs with each other, which further helps the programme’s leaders like her to shape policies and programmes that enable a good work-life balance.

Grateful that she hasn’t had to challenge any stereotypes related to gender dynamics in her role,

Dr Mahmood credits this to directives in her workplace that support gender equality, and to the culture of her individual team. These attributes have blended to create an equitable environment where everyone can use their abilities.

Sharing rare, much-needed skills

Chief of the Laboratory of Clinical Virology in the Pasteur Institute of Tunis, Professor Henda Triki makes a concerted effort to share her knowledge with others. Her altruistic spirit goes beyond her laboratory, especially as her specialty of work is still rare in North Africa: She teaches virology at the Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, and constantly keeps an eye on how best to upgrade her team’s skills and technology at work.

Professor Henda Professor Triki has a collaborative leadership style at work, which results in her sharing her team-building skills with her colleagues – which has helped them address challenges many times before, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. Amidst the chaos and anxiety during the pandemic, Professor Triki and her team had strong moments of solidarity and collaborative work.

Professor Triki wants her fellow female colleagues to be proud of working for the polio eradication programme, as it offers great opportunities. It has allowed women to distinguish themselves from others by acquiring skills that other laboratories do not have. She is pleased to note now that there are many women who are the face of specialized laboratory work in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.

This year, the UN’s theme for International Women’s Day is ‘DigitALL: Innovation and technology for gender equality’.

Originally published here.