On 27 March 2014, India was officially certified wild polio-free. This pivotal moment not only marked a triumph for the country itself, but as the last country battling the virus in the WHO South-East Asia Region (SEARO), it also paved the way for the entire SEARO region to be certified wild polio-free—a massive undertaking for the world’s largest region, spanning from India to Indonesia.

As we celebrate the 10-year anniversary of this triumph, we catch up with a few experts who worked on polio eradication India – Deepak Kapur (Chairman, Rotary International’s Polio Plus Committee), Dr. Roma Solomon (Former Executive Director, CORE Group Partners Project India Secretariat), Dr. Jay Wenger (Director, Polio, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), and Dr. Naveen Thacker (President, The International Pediatric Association). Their reflections serve to remind us of the collective will and commitment that made overcoming a seemingly insurmountable health challenge possible.

What was your role in the fight to end wild polio in Southeast Asia/your country?

As a young pediatrician in 1994, I witnessed the devastating effects of a polio outbreak. Motivated to make a difference, I embarked on what became a lifelong mission to combat polio. I advocated for polio eradication by authoring informative booklets and books that were distributed across the country and collaborated with my fellow Rotarians to raise awareness and resources however we could, which once included sending handwritten postcards to pediatricians and Rotary clubs. Following over a decade of these kinds of grassroots efforts, I then began working to shape the policies that would eventually help India eliminate wild polio.

Describe a time you felt up against immense barriers in the fight to end wild polio in your area, and what helped you remain optimistic.

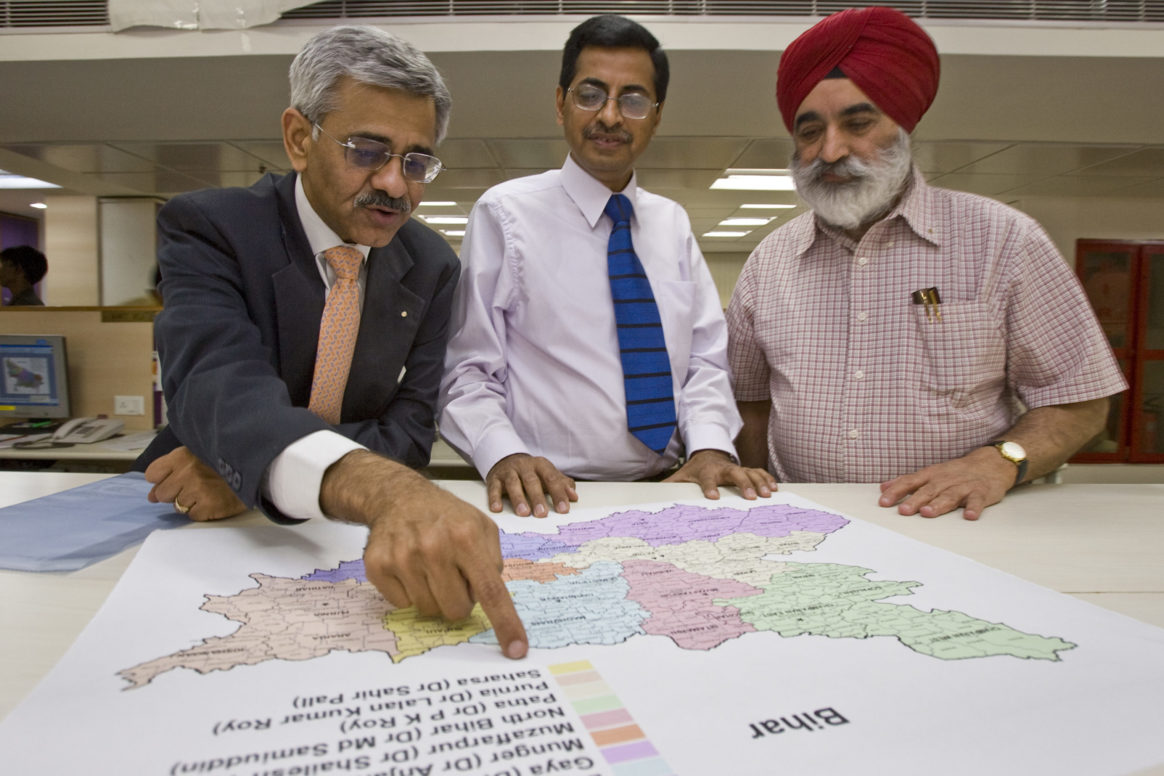

We were facing fierce resistance against vaccination in Uttar Pradesh, when I recalled meeting Moosa Kaka. Moosa Kaka came to me when I was working in his hometown of Kandla to ask about vaccinating his children, instead of relying solely on religious leaders from his mosque. Remembering his heartfelt plea for reassurance, it dawned on me that healthcare providers play a pivotal role in addressing vaccine hesitancy and instilling trust in communities. This realization spurred us to establish a network of pediatricians and medical professionals. Once we saw how successful this was in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, I knew it was only a matter of time and refining our strategy before the whole country would be wild polio-free.

What is a key lesson from the fight to end wild polio in your area that the rest of the world can learn to help stop the virus globally?

While it is hard to pick one, a crucial lesson from India’s fight against wild polio is the power of partnerships. At a global level, India ensured their strategies were aligned with the global effort to fight polio, from new innovations to timely disease surveillance to involving female staff in vaccination teams. In the country, coordination with the private sector was critical to our success. Even at a local level, we actively engaged the community and worked with socioreligious leaders to address social resistance.

What does it mean to you that your area is still wild polio-free 10 years later?

This holds significant meaning for me because of the years of dedication we’ve put into our work. While we acknowledge the ongoing risks, we are committed to maintaining vigilant surveillance, which is of great importance to me.

What was your role in the fight to end wild polio in Southeast Asia/your country?

This holds significant meaning for me because of the years of dedication we’ve put into our work. While we acknowledge the ongoing risks, we are committed to maintaining vigilant surveillance, which is of great importance to me.

Describe a time you felt up against immense barriers in the fight to end wild polio in your area, and what helped you remain optimistic.

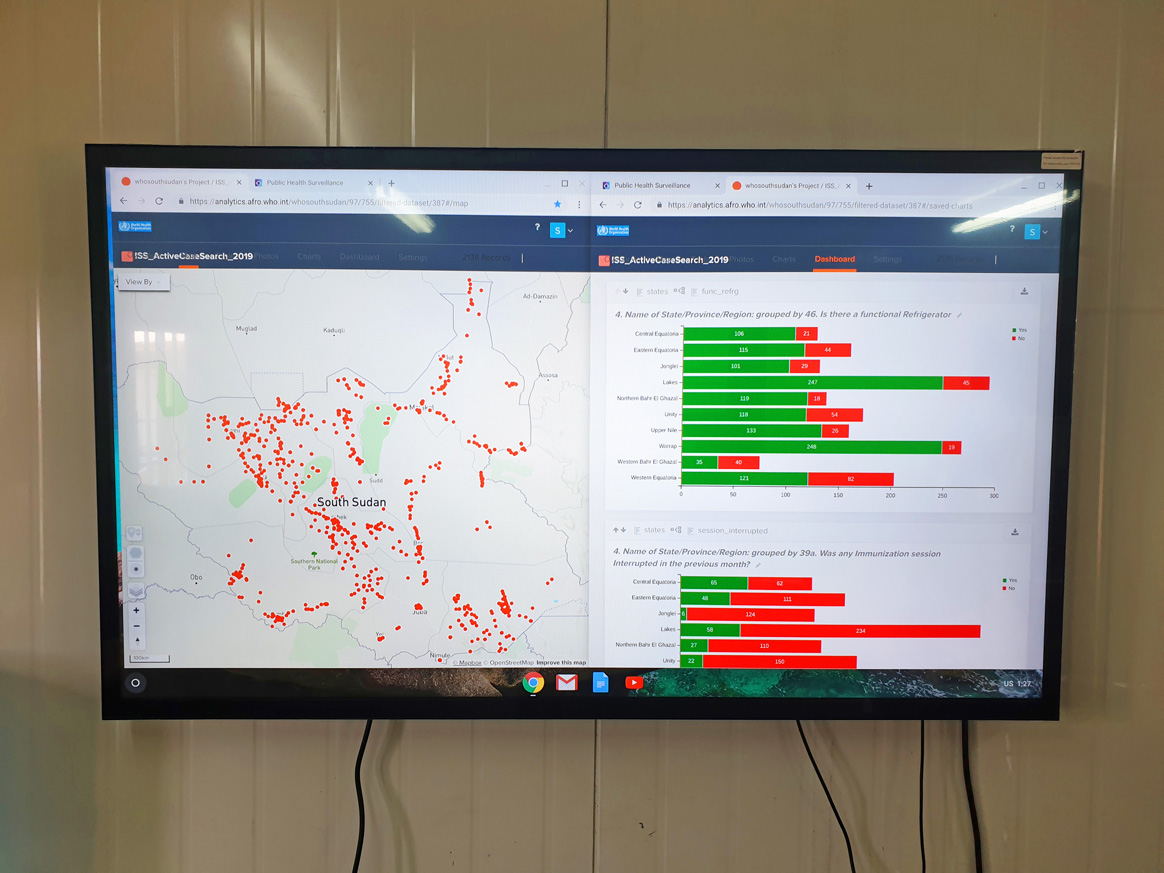

Ensuring accurate surveillance systems throughout all parts of India, including places where there was not a strong healthcare infrastructure, presented formidable challenges. The tireless workers of NPSP – Indian physicians, drivers, administrative support staff and other – were essential to overcoming these barriers. This was all supported by the unwavering dedication of our advocacy partners like Rotary, as well as by the Government of India. Their commitment played a pivotal role in overcoming obstacles, increasing support for the polio program and advancing our surveillance efforts to every corner of the country.

What is a key lesson from the fight to end wild polio in your area that the rest of the world can learn to help stop the virus globally?

Commitment from government partners at all levels was crucial to success. Government commitment that consistently translated into action at the operational level – from country-level officers to district administrators – identifying programmatic gaps and challenges and then committing to urgent evidence-based course-corrections was a critical characteristic of the final stages of polio eradication.

What does it mean to you that your area is still wild polio-free 10 years later?

Knowing that countless children have been spared from this debilitating disease is a remarkable feeling, and I feel fortunate to be a small part of the global community that contributed to a polio-free India. In the past decade, the infrastructure built by the polio program has evolved to strengthen health systems for a number of issues – for example, responses to diseases like measles, rubella and COVID-19 utilized surveillance systems built out by the NPSP. Seeing what we were able to accomplish in India motivates me to work to stop polio transmission globally, so no child has to live in fear of paralysis from this preventable disease.

What was your role in the fight to end wild polio in Southeast Asia/your country?

I led the CORE Group Polio (Now known as ‘Partners’) Project (CGPP) India Secretariat from its inception in 1999 until retiring last year. My work with CORE focused on community engagement to achieve polio elimination in India.

Describe a time you felt up against immense barriers in the fight to end wild polio in your area, and what helped you remain optimistic.

On one of my field visits, the community mobilizer led me to what we called a refusal household. I saw a woman my age washing clothes in the open veranda. As soon as she saw me, she ran inside and picked up a little girl and asked me to leave. I sat down beside her and started a conversation with her, trying to find out the reason why she did not want her grandchild to get vaccinated. To my surprise she started crying and told me that she had just lost a grandson because he was given some injection by a local ‘doctor’ for ‘fever’ and she didn’t want to lose this child too. The community mobilizer and I spent the next half hour with her, explaining how the polio vaccine works and how it would protect this child and not harm her. She agreed to not only vaccinate the little one but also spread the word among her friends and neighbors.

What is a key lesson from the fight to end wild polio in your area that the rest of the world can learn to help stop the virus globally?

As medical professionals, it’s vital that we must leave our egos at the door and keep compassion, empathy, and social justice at the forefront of our minds. Mothers who deny interventions that would benefit their children often come from a different background than our own. It is our failure if we cannot convince them or understand the reason behind their refusal. Refusals need time to change toward acceptance.CGPP India served as a liaison between the government and civil society, so we saw firsthand how polio work brought a certain sense of unity among all development partners. The virus brought us together with one single purpose: to work together to protect our children from it. We were forced to look at the disease from a human angle and from the parents’ point of view. This helped us realize that unless we involve people for whom this program is intended, it will not work. It is a people’s program.

What does it mean to you that your area is still wild polio-free 10 years later?

While I am thrilled to have reached this milestone, I am both fulfilled and unfulfilled in seeing how far this work has come. The world needs to work harder and faster before the virus re-emerges in polio-free areas. It can spread like wildfire and threaten years of hard work. Somehow, I feel that the world is not very aware of the progress made and the efforts that have gone into the program so far. This fight needs to be won as soon as possible.

What was your role in the fight to end wild polio in Southeast Asia/your country?

My fight against polio in India started way back in 1995 during the first immunization drive (NID). Back then, Rotary played a key role in convincing the Indian government to adopt the National Immunization Day which was inspired by successful programs in Brazil and other countries. My involvement with the polio eradication efforts of Rotary further intensified in the year 2001 when I was appointed as the chair of Rotary International’s India Polio Plus Committee (INPPC). I’ve held this position for 23 years now and I hope that not only our region, but the entire world will be completely free of the wild poliovirus (WPV).

Describe a time you felt up against immense barriers in the fight to end wild polio in your area, and what helped you remain optimistic.

There were many occasions over the years where the partnership consisted of WHO, UNICEF, CDC, and Rotary was literally up against the wall, as there were immense barriers on the way. One such challenge arose when we were alternating supplementary immunization rounds between the monovalent oral polio vaccine type 1 (mOPV1) and monovalent oral polio vaccine type 3 (mOPV3). After these campaigns, we started to notice a seesaw effect: focusing on one type of polio would lead to a rise in cases of the other. When we were concentrating on the rounds of the mOPV1, WPV3 cases would rise and vice versa. However, this issue was eventually resolved with the introduction of the bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine (bOPV) which contains only two components: attenuated live viruses of the WPV1 strain and the WPV3 strain. This formulation eliminated the WPV2 strain from the vaccine which had previously reduced its efficacy. With the bOPV, we were able to simultaneously address the outbreaks of WPV1 and WPV3, particularly in the northern states of India.

What is a key lesson from the fight to end wild polio in your area that the rest of the world can learn to help stop the virus globally?

The battle against polio in India has provided us with numerous invaluable lessons. One of the key lessons is the never-say-die attitude. Another one is the power of partnership and what it can achieve, as demonstrated collectively by WHO, UNICEF, Rotary, and the Government of India. Perhaps, the most important lesson that we have learned and that can be used for other health and social endeavors not only within our country or our region but across the world, is that all movements must be converted into people’s movements. When the beneficiaries themselves start demanding immunization or vaccines and when they recognize and appreciate the value of what we’re offering for free- that’s when a program transforms into a people’s movement and then the success is assured.

What does it mean to you that your area is still wild polio-free 10 years later?

Leading global experts had predicted that India would be the last country to eradicate polio. However, we proved them wrong, recording our last case of the wild poliovirus on January 13th, 2011 and maintaining our polio-free status for three years to achieve our certification as a polio-free nation on March 27th, 2014. The key to our decade-long success in remaining polio-free lies in two basic strategies. First, our intense immunization efforts ensured nearly every child under the age of five received either the polio drops or the injectable polio vaccine. Second, our exceptional surveillance system, conducted by the National Polio Surveillance Project (NPSP), a joint venture between the Government of India and WHO, provides world-class monitoring and surveillance for polio cases. These strategies have been instrumental in not only achieving but also maintaining our polio-free status till date.