On 19 January 2023, representatives from the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the Ministry of Health of Syria concluded a three day joint mission on polio transition planning.

The team conducted various meetings with national counterparts, United Nations agencies and other stakeholders to assess the current situation, and identify the needs and resources required to maintain polio-essential functions and strengthen routine immunization to maintain Syria’s polio-free status. As part of the mission, the team agreed on the way forward to design a roadmap to support and sustain the ongoing integration of polio assets to ensure long-term benefits for immunization and emergency response.

While Syria is a polio-free country, it is at very high risk of imported polio outbreaks. In the last decade, the country experienced two polio outbreaks, including an outbreak of wild poliovirus following an importation from Pakistan in 2013, that paralyzed 36 children. In addition, a 2017 outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) left 74 children paralyzed. In both cases, the country managed to contain the poliovirus and stopped the outbreak in less than a year using intensive polio vaccination campaigns and surveillance.

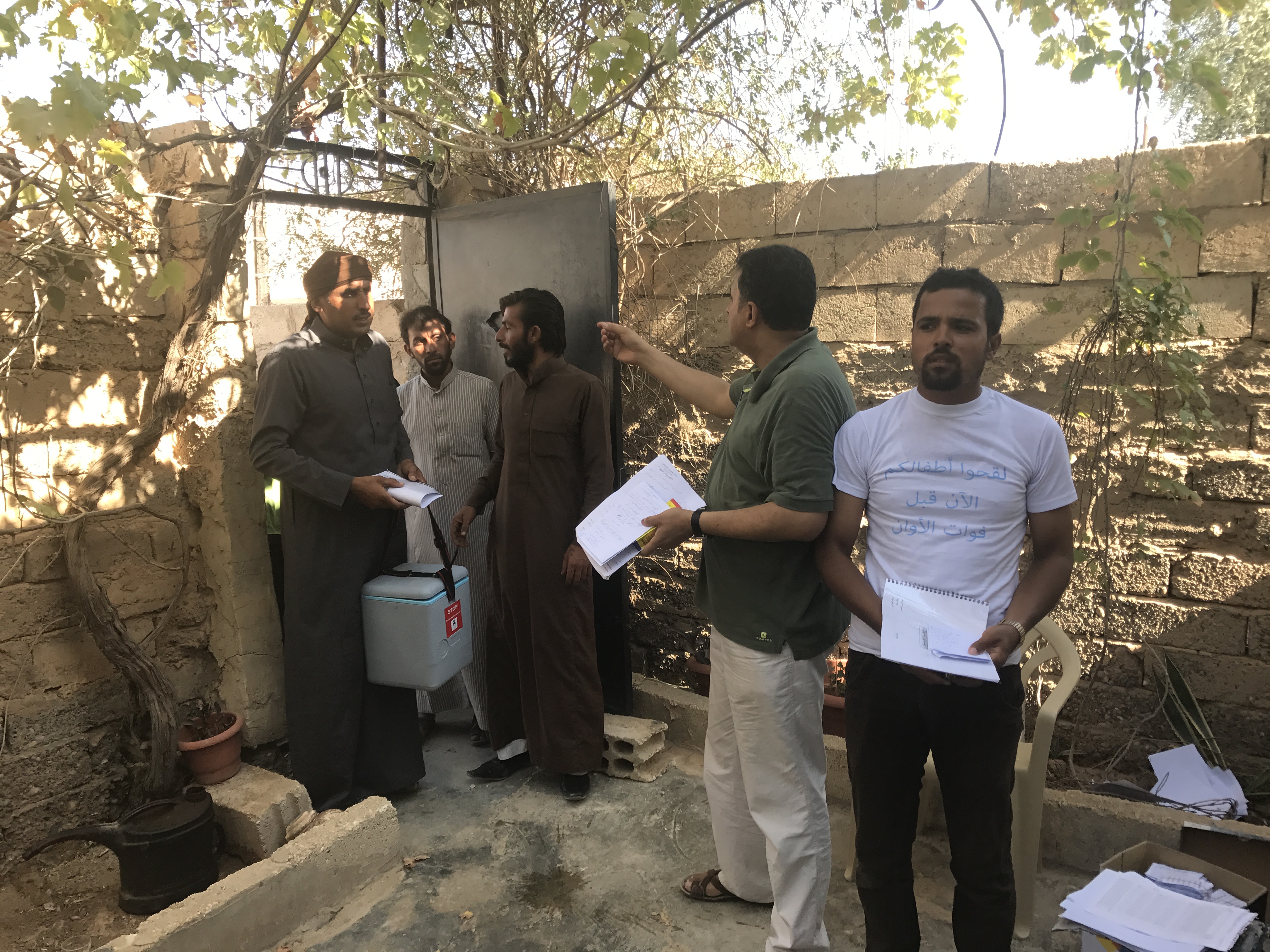

WHO is working closely with the Government and other stakeholders to maintain highly sensitive surveillance for polio and capacities to detect and respond to polio outbreaks swiftly. Furthermore, WHO and UNICEF are supporting the country to leverage the capacity and rich legacy built from years of polio operations to strengthen the essential immunization programme and capacities to detect and respond to other disease outbreaks.

“The main goal of this mission is to ensure that the polio essential functions are well preserved,” said Dr Rana Hajjeh, Director of Programme Management at WHO’s Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. “We at WHO emphasize the importance of strengthening essential programmes like the national routine immunization and also strengthening the emergency response to take advantage of all the polio assets and building health systems. Overall, Syria has integrated polio functions very well in their national immunization programme and we will do our best to continue supporting them as needed,” she added.

Polio essential functions are managed by the Ministry of Health, with the technical and logistical support of WHO. Given the importance of ensuring the sustainability of functions, with support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, both partners have been able to cover critical programme needs pertaining to routine immunization, including polio.

“While protecting the success achieved in containing the poliovirus outbreaks in record time, we should combine our efforts at all levels to maintain the high levels of immunity of the Syrian people against this life-threatening disease,” said Dr Iman Shankiti, WHO Representative a.i. for Syria. “WHO is working closely with the Ministry of Health and all other partners to resume the robust immunization programme in Syria,” she added.